The 59th Commission on the State of Women in New York attracted 8500 people from all over the world to discuss the rights and challenges of women. I was invited by the Norwegian Anti Discrimination Ombud to join a panel on gendered hatespeech. This is what I said.

(red anm: på engelsk fordi jeg er for lat til å oversette den tilbake til norsk)

Hi – thank you for having me, and thank you to Anti discrimination ombud for setting up this panel and bringing attention to this topic.

So, I am going to talk about gender, hatespeech and video games. And over the next 10 minutes I hope to answer three questions; The first is how is sexual harassment experienced in video games? Secondly, How is it explained? And finally; What can video games teach us about lawful gendered hatespeech and harassment?

But let me start with a few words about games. Gender and games is not a new topic. With more than 2 decades of research it’s fairly well established that video games are rift with sexist designs, sexist marketing and sexist role models. The overt sexism in games perpetuates the idea that video games are toys for boys. And while it is true that video games are a very popular past-time among men, it is really just a very popular past-time all together.

We spend 3 billion hours a week playing video games. 96% of kids under 18 play games and more than half of adults. Games are a lifelong interest, and as we move past media panics about the possible negative effects – we are starting to see the positive. Video games are used in schools to increase learning and by health professionals to motivate treatment. Video game art is displayed at the Smithsonian, and philharmonic orchestras record and perform tributes to video game scores.

Video games has moved from sub culture to main stream. But we keep using the horrid stereotype of the basement dwelling virgin when we talk about gamers.

Which is not helpful.

So lets set the record straight; 48% of players are female, and there are more women 40+ playing video games than there are young men.

However, young men still spend more time and money on games and have until now held position as favored customer demographics. And regardless of games now being a mainstream phenomenon, the gamer identity is still tied closely to an experience of being an outsider. Of being ridiculed for your hobby and never given a seat at the “cool kids table”.

Exactly because so many gamers have experienced exclusion themselves, it has been disappointing to see this culture take online harassment to new levels – and to defend it with such vigor.

Gamergate – a primer

I am here referring to Gamergate.

If you don’t know what Gamergate is, that is ok. No one really does. In part because so much of the debate are attempts to define what gamergate actually is about.

Depending on whom you ask you will get very different answers about the meaning of Gamergate. For those who identify with the movement, it is a consumer revolt reacting to corruption in video games journalism, critiquing too close ties between producers and reviewers.

For pretty much everyone else, Gamergate is about gendered harassment. For one, the whole controversy was sparked by a jilted ex-boyfriend who accused indie game developer Zoe Quinn for sleeping her way to good reviews. The accusation was disproved in about 10 minutes, but it didn’t stop the outrage. Gamergate escalated already existing tensions about gender, inclusion and harassment in game culture, and those who spoke up against Gamergate, or simply advocated more diverse game design, found themselves targets. And, in the fall of 2014 at least 4 different female game developers and writers had to leave their house out of safety for their lives.

Anita Sarkeesian, who has been the target of this for years, describes it as a cyber mob. We are talking hundreds if not thousands of people participating in the harassment. The massive coordinated hate campaigns are coordinated on various forums, with targets and goals made explicit through so called “operations”.

The attacks combine hacking of social media and releasing of personal information with extensive slander. This includes unlawful edits of personal wiki pages where someone would change occupation from game designer to prostitute, to contacting employers and demand that they be fired. At the far end of the scale we see rape, bomb and death threats.

Zoe Quinn, the woman accused of sleeping around for positive reviews, became the first target of Gamergate and described how this felt:

« For the first five days, I couldn’t sleep. Every time I would start to doze off, I’d be shocked awake from half-asleep nightmares about everyone I love buying into the mob’s bullshit and abandoning me. The ceaseless barrage of random people sending you disgusting shit is initially impossible to drown out — it was constant, loud, and it became my life. Of course I know that this is just a small minority of the angry and disenfranchised, but I felt like it was the entire world. That’s how it works — they use sheer volume and repetition to make their numbers seem overwhelming.”

The kind of harassment that Quinn, and other public figures in the game world have experienced, is harrowing. It is a terrifying reminder of what can be achieved when the same kind of technology and know-how that makes crowdsourcing possible, is used to destroy people’s lives.

Luckily most players are not the target of cyber mobs. But harassment is sadly a part of many gamers’ lives. So I am now making a shift to talk about how players themselves experience and explain gender based harassment based on a multi method research project. Our findings are based on an online survey of 935 respondents, qualitative interviews with 8 expert players and a media analysis.

How players experience harassment

Our data supported earlier research that show how playing online as a highly gendered experience. While we used to think that going online meant freedom to be whoever we wanted, it is becoming painfully clear that is not the case.

Female players have to deal with prejudice on a daily basis, prejudice that says that female players are bad at playing games, that they only play because they want attention from male players, or that that they only play because their boyfriend plays.

The othering of female players is distinct and extensive, and sexual harassment is part of this.

So let us look at what forms it takes. We have:

- verbal sexual harassement (i’ll come back to this),

- visual sexual harassment, like being exposed to sexist game design or using addons to remove the clothes of fellow players against their will

- Unwanted sexual advances; requests for naked pictures or cybersex, or impromptu details of sexual fantasies

Unlike with Quinn, Sarkeesian and other public female gamers, for most people harassment does not eclipse play. It is not EVERY time you log into a lobby, or EVERY time you tell someone you are a woman.

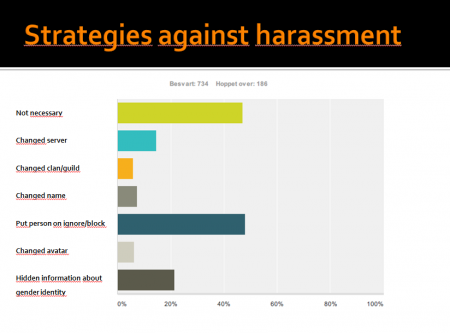

However, it is pervasive enough to shape what female players feel they can and cannot do in game. This is telling when we asked about what strategies they used to protect themselves from harassing behavior.

Frequently used strategies was to report, to block or to move to another server. More so : They integrated it into the play experience; it influenced what games they played, if they played online or offline, if they solved quests in groups or alone and what kind of guilds they sought out. Several noted how they made sure to bring a guy friend to protect them in case someone get uppity.

Quite telling of how toxic this culture could be, we found in the question “hidden information about gender identity”. Over half of our female respondents had at some point been «in the closet» about being a woman. Being in the closet is what you do when you are afraid for sanctions against your identity, and these players felt that the overall environment was so hostile that it made more sense to pretend to be a man.

So that was a look into the experience of sexual harassment, let’s look at the explanations. After all, how can anyone justify this kind of behavior to themselves?

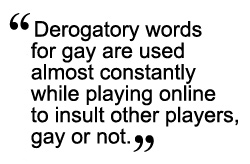

Our survey showed that sexually harassing language like slut, faggot and rape metaphors were pervasive, together with racist, ableist slurs or comments about your mother being ……up to something. Up to 80% had seen words like homo and retard used, while about 55% had seen whore, slut and pussy . So basically harassing language was highly prevalent, and honestly; something we expected to find.

What did surprise us was when we asked if they saw this kind of language as problematic – and we got a 50/50 response.

For half of our players, this was not a problem – why?

How players explain harassment

Three answers crystallized as explanations for why they didn’t mind this kind of harassing language, and in some case saw it as desirable

- The first was an idea that what happens in games are completely separate from the rest of the world. They would explain that words simply have different meanings, and that there was no overlap between games and offline lives.

- Gay in games doesnt mean homosexual. It means something sucks»

- «They are different communites. Its a total disconnect from reality»

- A second explanation was freedom from political correctness; that pressing play was to enter a space in which they can escape the tripe of everyday life

- «Day in and day out i’m kicked around by life and i come home and pop in a game to forget about the world.”

- A third explanation is that it’s part of game culture; binding game culture and harassment together as something inseparable – as if one could not exist without the other.

- «Complaining about bad language and harassment in video games is like going to a rap concert and complain about all the swearing»

All three explanations are provably wrong or just deeply flawed; online harassment does affect your offline life, the freedom some gamers experience by brash and egging behavior is at the cost of someone else’s enjoyment, and there is nothing inherent in games or game culture that means harassment is a necessary component.

So we have seen that harassment goes from online to offline, how it impacts players lives and their freedom to express themselves and to feel safe. Secondly we have gotten a look into the rationale player’ boast. I have now reached the final question: What is the take away?

What can we learn about harassment by studying gamers?

First of all we learn that context matters. It matter for how harassment is performed and how we may solve it.

When the context is video games there are particular challenges, and particular solutions that emerge. We know that video games foster competitiveness, they are often anonymous –and much of the fiction is related to violence and aggression. These are factors that may increase the frequency of harassing behavior.

On the other hand game culture also have elements that we can work with, like how games have explicit goals, and explicit reward/punish systems. Mechanics that support moderation and change.

The second lesson I learned, was not so much from research but from talking to gamers – and gamergaters, over the last 6 months. The narrative that i present in which the straight white male gamer is privileged, and the female gamers are discriminated, is one they cannot relate to at all. From their lived experience they are the ones who are marginalized, they experience harassment (and they do) – while female gamers get ‘preferential treatment’ and the kind of attention (sexual) that they themselves wish for.

Why male gamers don’t notice the privilege they have is another discussion, but so far I have found the «check your privilege» attitude works poorly when talking to people who identify as the underdog.

As a last and final lesson from the world of video games, I want to point out how there are those with vested interest in keeping up with harassment. I am talking here about YouTube celebrities, Twitter personas and bloggers who make profit out of generating hateful content that fuels movements like Gamergate. There are people making a living out of videos with titles like «Why feminism poisons EVERYTHING» (everything in caps) or «Sarkeesians massacre threats, real or fake?». Or this documentary pictured on this slide, in which they are making a movie about how Anita Sarkeesian has faked victimhood for money.

With such dire stories it can be hard to be hopeful, but even though the lessons from video games might be grim. But, It is not all bad.

People play in spite of harassment. People make games in spite of harassment. People love games in spite of harassment.

And when someone cares to say «enough is enough», it has effects. League of Legends was known as the worst of the worst when it came to player harassment, but the company took charge and implemented anti-harassment strategies. The result?

Simple changes like having to opt-in to chats reduced harassing behavior by 30%, and repeat offenders were drastically reduced when the justification of their suspension was spelled out. They were able to change the toxic culture infusing their game.

So, while there are clearly some solutions that are better than others, it seems doing something is a very, very good start.

So let’s play.